One way of preserving foods, but also for “present use” [Hale] was by potting. Many cookery books from the 18th (almost twenty) into the 20th century contained a variety of recipes - Robert Smith [1723] had eleven, and Beeton [1863] had many more. ...

One way of preserving foods, but also for “present use” [Hale] was by potting. Many cookery books from the 18th (almost twenty) into the 20th century contained a variety of recipes - Robert Smith [1723] had eleven, and Beeton [1863] had many more. ...Underwood Deviled Ham and Armour Potted Meat are available in supermarkets, but with far less demand than in the past. [photo from Steppes Hill Farm Antiques website]

Various foods were potted including meats (ham, beef, veal, tongue, game), poultry (chicken, turkey, swan), small birds (woodcock, quail, lark, pigeon), fish (char, tench, trout, eel) shellfish (lobster, crab, shrimp), mushrooms and cheese(also called Pounded Cheese). Interesting versions were "To pot Beef to eat like Venison," a receipt for a goose within a turkey, and “To pot Boned Pigeons whole.”

Generally, the meat or fish was cooked, boned, cut against the grain, then pounded in a mortar with salt, pepper, and spices, such as mace, nutmeg and cloves. In

1817 Kitchiner wrote "...to make Potted Meats smooth there is nothing equal to plenty of Elbow-grease." It should be the consistancy of paste or "like dough" [E. Smith] Once cooled, the mixture was firmly pressed into a potting pot and sealed from the air with a layer of clarified butter. The pot was covered with paper, sheet India rubber, or a bladder tied securely in place and stored in a cool dry location for months. Earlier recipes for pounded meats (or pieces) put the mixture in hard pastry shells to be served. By mid 1600’s some pots were mentioned. Price’s The Complete Cook, 1681 suggested the paste cover an earthenware pot.

1817 Kitchiner wrote "...to make Potted Meats smooth there is nothing equal to plenty of Elbow-grease." It should be the consistancy of paste or "like dough" [E. Smith] Once cooled, the mixture was firmly pressed into a potting pot and sealed from the air with a layer of clarified butter. The pot was covered with paper, sheet India rubber, or a bladder tied securely in place and stored in a cool dry location for months. Earlier recipes for pounded meats (or pieces) put the mixture in hard pastry shells to be served. By mid 1600’s some pots were mentioned. Price’s The Complete Cook, 1681 suggested the paste cover an earthenware pot.With the advent of pots, the potted food could be sent “... to table either cut in slices or in the pot.” [Farley] “If you want to turn it whole out of your pots, butter them well before you put in the meat.” [Briggs] An attractive slice was “Potted lobster or Crab” by Kitchiner made by layering lobster pieces, coral and spawn. Glasse wrote that "...a slice of this ['potted Cheshire Cheese'] exceeds all the cream cheese that can be made."

In addition to being served during the meal, potted foods could be used to thicken soups, to make sandwiches, for those unable to chew their food and for travelers.

Potting was not always a foolproof way to store food. Glasse included a recipe "to Save potted birds, that begin to be bad... [and] that no body could bear the smell for the rankness of the butter.."

The potting pots were earthenware or fine china. Receipts specified sizes from small to large, and round or long. Perhaps the finer containers were for immediate use on the table, while the earthenware served for long term storage.

Several Chesapeake colonial probate inventories listed potting pots in china and earthenware. The famed Virginian Peyton Randolph's estate in 1775 had two as part of a Blue and White China set with a Tureen, 11 dishes, 4 Sauce boats, 2 Potting Pots, 13 Coffee Cups & Saucers, and 18 plates. [Gunston inventories online]

Porcelain companies in England produced potting pots from the 1740s until the mid 1780s. In a c1755 pricelist from the Worcester China Warehouse in London, prices for three sizes of “potting pans” by the dozen were 6/ , 9/ and 12/ . “Potting pots and covers, white, oval, basket weave at 2/6 per dozen.” [Darling]

China was r

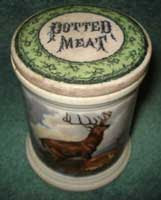

eplaced by various types of glazed pottery, produced in large numbers in northern England, into the 20th century. A charming specialized shallow

eplaced by various types of glazed pottery, produced in large numbers in northern England, into the 20th century. A charming specialized shallow  pot contained char, [photo from Fitzwilliam Museum] a fish from the Lake District of England, while the taller, lidded one with a picture of a deer contained potted meat.

pot contained char, [photo from Fitzwilliam Museum] a fish from the Lake District of England, while the taller, lidded one with a picture of a deer contained potted meat.To pot a Swan

Bone and skin your Swan, and beat the flesh in a mortar, taking out the strings as you beat it; then take some clear fat bacon, and beat with the Swan, and when 'tis of a light flesh-colour, there is bacon enough in it; and when 'tis beaten till 'tis like dough, 'tis enough; then season it with pepper, salt, cloves, mace, and nutmeg, all beaten fine; mix it well with your flesh, and give it a beat or two all together; then put it in an earthen pot, with a little claret and fair water, and at the top two pounds of fresh butter spread over it; cover it with coarse paste, and bake it with bread; then turn it out into a dish, and squeeze it gently to get out the moisture; then put it in a pot fit for it; and when 'tis cold, cover it over with clarified butter, and next day paper it up. In this manner you may do Goose, Duck, or Beef, or Hare's flesh. [E. Smith 1739]

Potted Beef.

Rub a piece of lean fleshy beef, about three pounds in weight, with an ounce of saltpetre powdered, and afterwards with two ounces of salt; put it in a pan or salting tray, and let it lie two days, basting it with the brine, and rubbing it into it each day. Then put the meat into an earthenware jar, just large enough to hold it, together with all the skin and gristle of the joint, first trimmed from it: add about a pint of water, put some stiff paste over the top of the jar, and place it in a slow oven to bake for four hours. When it is done, pour off the gravy, (which save to use for enriching sauces or gravies,) take out the gristle and the skin; then cut the meat small, and beat it in a mortar, adding occasionally a little of the gravy, a little fresh butter, and finely powdered allspice, cloves, and pepper, enough to season it. The more you beat and rub the meat, the better, as it will require so much less butter or gravy, which will assist it to keep the longer; but when potted beef is wanted for present use, the addition of gravy and butter will improve its taste and appearance. When it is intended for keeping, put it into small earthenware pots or into tin cans, press it down hard, pour on the top clarified butter to the thickness of a quarter of an inch, and tie over it a piece of damp bladder.

To make potted meat more savory, you may beat up with it the flesh of an anchovy or two, or a little minced tongue, or minced ham or bacon; or mushroom powder, curry powder, a few shalots, or sweet herbs of any kind, the flavor of whichever may be most agreeable. [Hale 1852]

Works cited

Beeton, Isabella. Book of Household Management. London: 1863

Belcher, George. Potted Char and other Delicacies. 1933. cartoon appeared in Punch magazine

Briggs, Richard. The English Art of Cookery. London: 1788

Darling, Trevor. “English 18th century porcelain potting pots and pans” in Northern Ceramic Society Journal UK 2002

Farley, John. The London Art of Cookery. London: 1787

Glasse, Hannah. The Art of Cookery. London: 1747

Hale, Sarah. The Ladies' New Book of Cookery. NY: 1852

Kitchiner, William. Apicius Redivus, or The Cook’s Oracle. London: 1817

Price, Rebecca. Complete Cook. 1681

Smith, E. The Compleat Housewife. London: 1739 9th ed

Smith, Robert. Court Cookery. London: 1725

Gunston inventories online: http://chnm.gmu.edu/probateinventory/search.php

©2010 Patricia Bixler Reber

hearthcook.com

No comments:

Post a Comment